|

Gastrointestinal Disorders in the GSD and Several

Other Breeds

by Fred Lanting Copyright

1990, 2003

Vomiting and gastritis

— Vomiting comes easily to dogs. Grass eating and

subsequent vomiting give rise to all sorts of

explanations, the most popular being that the dog

was sick and ate the grass to help him throw up.

Actually, excess grass is more likely the reason for

the reflex action. Dogs mostly eat grass because

they like the taste of it, just as with the case of

garbage, but it does appear that individuals learn

that too much can cause vomiting, so the intentional

eating of grass to induce vomiting may come after

experience. Gastritis, an inflammation of the

stomach lining, can be caused by the ingestion of

too much grass, garbage, or indigestible materials.

It can also be caused by viral or bacterial

invasion, but much more common, especially in pups,

is the presence of endoparasites: tapeworms,

roundworms, hookworms, whipworms, and coccidia.

Actually, tapeworms or roundworms can fill up the

belly to the extent that they back up and cause

vomiting from sheer bulk. The initial treatment for

gastritis or vomiting may be the withholding of food

and administration of Kaopectate every four hours.

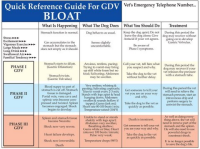

Torsion

— Commonly called bloat, sometimes described as

gastric dilation/volvulus (GDV), this is a terrifying and

frequently fatal disorder that German Shepherds and

many other deep chested dogs experience. A twisting

of the entrance and exit to the stomach traps the

food and gas. As the stomach swells, the twist is

more unlikely to be relieved without veterinary

help. Great strides in surgical treatment have been

made, but the key to reducing the high mortality is

still time. Recognize the symptoms and get the dog

to a veterinary surgeon, preferably an emergency or

trauma-oriented hospital. Simple dilation (swelling

due to gas) may not be serious as long as the dog is

able to pass food into the duodenum, but it has been

estimated that 80 percent of all dogs that

experience simple dilation will someday also have

torsion.

Symptoms of torsion

include a swollen, turgid abdomen; the sluggish

action of the dog; his white, frothy, unsuccessful

attempts at vomiting; and perhaps his scratching in

the dirt to make a cool hole in which to lie down.

Also, the spleen will feel like a hard lump. The

spleen is normally wrapped around some of the

stomach and therefore splenic torsion usually

accompanies gastric torsion, sometimes occurs

without stomach torsion. When either happens, the

return of the blood that flows through the spleen is

shut off, causing shock, the “immediate” killer.

The first thing your

vet is likely to do is attempt to push a tube down

the throat into the stomach so the gas pressure can

be relieved. If he cannot get past the twisted part

of the alimentary canal, he may opt for immediate

surgery so he can untwist the organs. One emergency

veterinary service in the Detroit area uses a

different kind of lavage tube in their treatment of

acute torsion. The large diameter, stiff, black

polyethylene pipe has a smaller, flexible tube

inserted into it. This smaller tube is for warm

water so that the stomach contents can be flushed

out of the larger one for about fifteen minutes. In

either case, once the dog has been stabilized,

decisions can be made about whether to operate, or

untwist a stomach or spleen still in volvulus.

Follow up surgical

techniques are numerous, but perhaps the one with

the most success in preventing future torsion is a

tube gastrostomy. In this procedure, a rubber or

vinyl tube is put into the stomach through the

abdominal wall, and in a week the stomach wall at

that point becomes attached with scar tissue to the

peritoneum and abdominal wall. The tube is then

pulled out. The surgical opening seals off in a few

days, and since the stomach is fused to the

abdominal wall, it is prevented from again twisting

out of position. Regular gastroplexy, which is

suturing the stomach to the abdominal cavity, is

also widely performed. Because of these and other

techniques, especially the rise of emergency

clinics, the mortality rates among those that make

it to the clinic while still alive has plummeted to

about 15 percent. Another 15 percent or so die

without being seen by the vet first.

Groups of scientists

at many locations have been studying bloat for a

long time, partly with help from such as Morris

Animal Foundation, the GSDCA, and many others. So

far, they have identified a number of likely

causative factors, including behavioral traits.

Breed susceptibility is pretty obvious, with 25

percent or more of Great Danes, Saint Bernards,

Weimaraners, and Irish Setters expected to suffer

from bloat sometime during their lives. German

Shepherd Dogs, Standard Poodles, Collies, and Gordon

Setters are fairly high on the incidence lists,

also. Some of the characteristics seen most often in

dogs that had bloated include some stressful event,

even minor, in approximately the eight hours prior

to the incident, a fearful temperament, and

consumption of fairly large quantities of non-food

material. The only dogs I’ve had direct contact with

that bloated were of impeccable character, but those

may have been in the minority. Purdue researchers

found no pattern in presoaking dry food or not, but

a slight correlation between several smaller meals

and less bloat. Others found no relation to soybean

meal in the food, an early target of breeders

looking for a primary cause. Adding vegetables and

canned or meat scraps appears to help lower

incidence. Most dogs (60%) bloated not immediately

after vigorous exercise soon after a meal, but in

mid- to late evening when resting or sleeping.

Less likely are other

types of torsion, but they can be as

life-threatening. Splenic torsion can occur without

gastric twisting, and an even more rare disorder is

mesenteric root torsion. The mesentery is the white,

fibrous, web-like or film-like tissue that connects

the various sections of intestines to each other and

to the abdominal wall. Blood vessels travel through

the mesentery, and if there is a twisting there,

regardless of whether the intestine itself is closed

off, the blood supply can be halted and the

intestinal tissue can become necrotic. Bloody

diarrhea, vomiting, abdominal swelling and/or pain,

and shock or general collapse can be symptomatic. It

may be the same as what some call “twisted

intestines”. So few dogs survive that it is

impossible to prevent recurrence or conclusively

predict whether those are at greater risk for

another attack than any other dog is.

There is a familial

element in torsion/volvulus in many, similar to the

way cancer “runs in families”, but most cases don’t

give a clue to hereditary factors. As in “toxic gut

syndrome” which is also seen a lot in some GSD

lines, it is almost impossible to tell which came

first, the presence of abnormal bacterial

populations and irritated intestinal or stomach

linings, or the bloat itself. Which is cause and

which is effect is not going to be easy or even

possible to determine. Some investigators suspect

that breeders may be stuffing their small, young

puppies’ stomachs too much, with results that show

up only later in life. Work goes on. Dr. Larry

Glickman and his group at Purdue University as well

as others have published several papers on this

syndrome. Dr. Glickman commented that the supposed

claim that raised bowls are correlated with

increased incidence in torsion/bloat may just mean

that this allows a dog to swallow more food (and

air?) more quickly than if they were on the floor. A

couple of website references, such as

<http://www.vet.purdue.edu/epi/bloat.htm>, had some

info, including from JAVMA’s Nov 15, 2000 issue. An

abstract follows:

Canine Gastric

Dilatation-Volvulus (Bloat)

School of Veterinary Medicine, Purdue University,

West Lafayette, IN 47907-1243

Non-dietary risk factors for gastric dilatation-volvulus

in large and giant breed dogs. Lawrence Glickman,

VMD, DrPH; N.W. Glickman, MS, MPH; D.B. Schellenberg,

MS; M. Raghavan, DVM, MS; T. Lee, BA

Summary of findings (references 1 & 2) -A 5-year

prospective study was conducted to determine the

incidence and non-dietary risk factors for gastric

dilatation-volvulus (GDV) in 11 large- and

giant-breed dogs and to assess current

recommendations to prevent GDV. During the study, 21

(2.4%) and 20 (2.7%) of the large and giant breed

dogs, respectively, had at least 1 episode of GDV

per year of observation and 29.6% of these dogs

died. Increasing age, increasing thorax depth/width

ratio, having a first degree relative with a history

of GDV, a faster speed of eating, and using a raised

feed bowl, were associated with an increased

incidence of GDV. Table 1 summarizes the magnitude

and direction of GDV risk associated with having

each of these factors. The relative risk (RR)

indicates the likelihood of developing the disease

in the exposed group (risk factor present) relative

to those who are not exposed (risk factor absent).

For example, a dog with a first degree relative with

a history of GDV is 1.63 times (63%) more likely to

develop GDV than a dog without a history of GDV. As

another example, if dog ‘A’ is a year older than dog

‘B’, then dog ‘A’ is 1.20 times (20%) more likely to

develop GDV than dog ‘B’.

|

Risk Factor |

Relative Risk |

Interpretation

|

|

Age |

1.20 |

20% increase in risk for

each

year increase in age |

|

Chest depth/width ratio

(1.0 to 2.4) |

2.70 |

170% increase in risk for

each

unit increase in chest

depth/width

ratio |

|

First degree relative with

GDV

(yes vs. no) |

1.63 |

63% increase in risk

associated

with having a first-degree

relative

with GDV |

|

Using a raised feed bowl

(yes vs. no) |

2.10 |

110% increase in risk

associated

with using a raised food

bowl,

contrary to popular opinion! |

|

Speed of eating (1-10 scale)

[for Large dogs only] |

1.15 |

15% increase in risk for

each

unit increase in

speed-of-eating

score for large dogs |

|

Most of the popular

methods currently recommended to prevent GDV did not

appear to be effective, and one of these, raising

the feed bowl, may actually be detrimental in the

breeds studied. In order to decrease the incidence

of GDV, we suggest that dogs having a first degree

relative with a history of GDV should not be bred.

Prophylactic gastroplexy appears indicated for

breeds at the highest risk of GDV, such as the Great

Dane.

OBJECTIVE: To identify non-dietary risk factors for

gastric dilatation-volvulus (GDV) in large breed and

giant breed dogs. DESIGN: Prospective cohort study.

ANIMALS: 1,637 dogs 6 months or older, of the

following breeds: Akita, Bloodhound, Collie, Great

Dane, Irish Setter, Irish Wolfhound, Newfoundland,

Rottweiler, Saint Bernard, Standard Poodle, and

Weimaraner.

PROCEDURE: Owners of dogs that did not have a

history of GDV were recruited at dog shows, and the

dog’s length and height and the depth and width of

its thorax and abdomen were measured. Information

concerning the dog’s medical history, genetic

background, personality, and diet was obtained from

the owners, and owners were contacted by mail and

telephone at approximately 1-year intervals to

determine whether dogs had developed GDV or died.

Incidence of GDV, calculated on the basis of

dog-years at risk for dogs that were or were not

exposed to potential risk factors, was used to

calculate the relative risk of GDV.

RESULTS AND CLINICAL RELEVANCE: Cumulative incidence

of GDV during the study was 6% for large breed and

giant breed dogs. Factors significantly associated

with an increased risk of GDV were increasing age,

having a first-degree relative with a history of GDV,

having a faster speed of eating, and having a raised

feeding bowl. Approximately 20 and 52% of cases of

GDV among the large breed and giant breed dogs,

respectively, were attributed to having a raised

feed bowl.

Another article based

on the same research but with slightly different

data pulled out for the particular subject matter,

was published in 1997: Multiple risk factors for the

gastric dilatation-volvulus syndrome in dogs: a

practitioner/owner case-control study (by): Glickman

LT, Glickman NW, Schellenberg DB, Simpson K, Lantz

GC. JAAHA, May-Jun., 1997. ABSTRACT: A study was

conducted of 101 dogs (i.e., case dogs) that had

acute episodes of gastric dilatation-volvulus (GDV)

and 101 dogs (i.e., control dogs) with non-GDV-related

problems. The control dogs were matched individually

to case dogs by breed or size, and age. Predisposing

factors that significantly (p less than 0.10)

increased a dog’s risk of GDV were male gender,

being underweight, eating one meal daily, eating

rapidly, and a fearful temperament. Predisposing

factors that decreased the risk of GDV significantly

were a “happy” temperament and inclusion of table

foods in a usual diet consisting primarily of dry

dog food. The only factor that appeared to

precipitate an acute episode of GDV [in their

observations] was stress.

This contradicted the

early-1990s study that indicated the opposite: that

raised bowls should reduce the incidence of

torsion/bloat. An article in “Bloat News” indicated

a possible link that raised feeders might help

prevent future episodes in a dog susceptible to

“aerophagic” bloat (linked to swallowing too much

air with the food, a commonly blamed cause at the

time. Another issue of the same periodical indicated

the single highest correlating factor was morphology

(body type). A graph showed a sharp incidence

increase as the depth of the chest exceeded its

width and a strong correlation with body condition

and temperament (weak nerves vs. calm, unstressed

dogs). It may be good to select dogs that have

strong, calm nerves, and are not slab-sided!

An article on the

Foster and Smith Pet Education site, “Interpret

Findings of a New Study on Bloat (Gastric

Dilatation/Volvulus - GDV) with Caution”, December

2000, at:

<http://www.peteducation.com:80/article.cfm?cls>,

starting with a subheading, “The Question of Raised

Food Bowls” circulated among fanciers. An excerpt:

“In this study, when analyzing the association

between the rate of GDV and the height of the food

bowl some questions arise. First, the study found

that large breed dogs whose food bowls are not

elevated have the lowest risk of GDV. A confusing

finding is that large breed dogs who have their bowl

raised over 1 foot have the next lowest risk, and

those who have their food bowl raised somewhere

between the floor and one foot have the highest

risk. So, the risk of GDV is not proportional to the

height of the food bowl. If height of the food bowl

is important, why doesn’t the risk steadily

increase, the higher the food bowl is raised?

Secondly, it appears that the researchers did not

consider the height of the animal in relationship to

the height of the bowl when looking for an

association between food bowl height and prevalence

of GDV. It would be of interest to compare the

height of the bowl to the height of the dog, since

dogs in this study varied widely in height due to

breed differences and age (some were only 6 months

old).

The third question is,

‘why weren’t similar findings obtained in giant

breed dogs?’ In giant breeds, dogs with food bowls

raised less than one foot had the same incidence of

GDV as those dogs who did not have their dishes

raised at all. Finally, it is unclear if the

researchers also analyzed whether the elevated

feeders were being used because other medical

problems were present or if the elevated feeders

could influence other factors such as the speed of

eating. Could these medical problems or other

factors, rather than the elevated feeders, have

contributed to the increase in GDV in this group? A

second subheading was ‘Comparison to Other Studies’:

The results of this study agree with most previous

studies, which also found that GDV increases with

age. On the other hand, in several studies, dogs who

ate faster had higher rates of GDV. In this study,

we had a peculiar finding: eating at a fast rate was

associated with an increased rate of GDV in large

breed dogs, but a decreased rate in giant breed

dogs. There have been other contradictory findings

in research on GDV. In some studies it was found

that overweight dogs had higher rates of GDV, and in

other studies, lean dogs had higher rates. In this

study, weight did not seem to make a difference. In

most studies, including this one, the rate of GDV

between males and females were similar; in one

study, however, males had an appreciably higher

rate.”

One other item that

was brought to light on a “VetMed” e-mail discussion

list, was that there is no proven advantage to

raised feeders, and that the Foster and Smith

company which runs the Pet Education website sells

many types of elevated feeders.

While some excellent

work on GDV has been carried out at Purdue, some

feel that very little research has been done in the

US on canine torsion/volvulus. Here are websites I

was told will give information on GDV; I have not

checked these out, so I cannot verify their

usefulness. Some may be “foreign links, as well as

human links and livestock links” as the person who

gave me this list said:

http://www.editoraguara.com.br/cv/ano5/cv29/cv29.htm#tormes

http://www.vetinfo.com/dbloat.html#MesentericVolvulus

http://www.canismajor.com/dog/bloat.html

http://www.harkleen.com/Chimo.htm

http://search.atomz.com/search/?sp-q=mesenteric&sp-a=000608a5-sp00000000

http://www.emedicine.com/emerg/topic311.htm

The huge retrospective epidemiological study of GDV,

as I mentioned above, is at Purdue, run by Larry

Glickman.

http://www.vet.purdue.edu/epi/bloat.htm The

project was funded by the AKC Health Foundation and

by breed clubs.

****************************************************************

Pancreatic Disorders

—Very close to where the stomach empties its

contents into the small intestine, ducts contribute

secretions from the gall bladder and pancreas,

mostly to aid in the metabolism of fats, which are

fairly resistant to action by gastric acid. If

either gland does not function properly, this can

result in loose stools, and inefficient absorption

of nutrients with highly variable severity.

The pancreas is a

rather long, V-shaped gland located near the

stomach, and aids the digestion of food. It has two

major types of cells or tissues. One group is

endocrine in nature, which means it secretes

hormones into the circulatory system, which in turn

transports them to other glands and body parts. The

endocrine activity of this gland serves to control

blood sugar level, and when defective, results in

diabetes. The other part empties a group of

biochemicals into the digestive tract. It produces

enzymes and bicarbonate, and excretes these into the

duodenum. One major enzyme, amylase, breaks down the

long starch macromolecules, while others break down

fats and proteins. Most GSD people, in America, at

least, are concerned more with the digestive

function than with diabetes. I have corresponded

with fanciers in England who are concerned about

pancreatic insufficiency, and since many of their

lines are from recent German imports, this is

possibly a more widespread problem there than I had

earlier suspected.

Clinical pancreatitis

— The word clinical may be used to mean “frank” or

“obvious”, at least to a veterinarian with the

training and equipment. Any disorder with “-itis” on

the end refers to an inflammation. Most causes of

this disorder are of unproven origin, but “bad

genes” must be the prime suspect. Adult clinical

pancreatitis is not tremendously common in the

German Shepherd Dog, but when it does occur it is

usually the middle aged, obese bitch on a fatty diet

that has it. Chronic pancreatitis symptoms include

emaciation, dull dry coat, and high appetite with

poor digestion as seen by fatty, loose stools

containing undigested starches. Treatment is aimed

mainly at correcting the diet, but it is very

difficult to control.

Pancreatic atrophy —

On the other hand, German Shepherd Dogs seem to have

a considerable predisposition to pancreatic atrophy,

also known as juvenile atrophy or pancreatic

insufficiency (PI), and certain bloodlines have been

much more associated with it than others. For years

I have referred to the milder manifestations as

subclinical pancreatitis, because people who are not

familiar with familial and breed tendencies are

likely to miss the subtle signs, and I had suspected

the two forms were variations of one basic problem.

The disease usually starts before the dog is one

year old, though many are three before symptoms are

noticed. When lack of “drive”, diminished coat

lustre, coprophagia, and/or poor weight are seen,

have the stool examined by your veterinarian for

abnormal fat level and absence or low level of the

trypsin enzyme. If the problem is discovered before

it becomes severe and chronic, Viokase™, a brand of

powdered raw pancreas, added to the food half an

hour or more before feeding usually produces good

results. Other similar products that I am familiar

with are called Pancreazyme™ and Prozyme™. I have

heard of a British product called Tryplase as well.

I was told, but have not verified this, that Prozyme

“is not the medication of choice as it only contains

the vegetable type enzymes.” Costs vary widely among

these. Getting enough to do the job without making

the owner go broke is a tough balancing act, though.

By the way, these types of preparations also appear

to be good for non specific diarrhea. I believe

there is a strong possibility that subclinical

pancreatitis can worsen with neglect into an acute

attack by enzymes on the pancreatic and surrounding

tissues themselves, and that this condition may be

the cause of many instances of diagnosed perforated

ulcers. Texas A&M vet school at one time was trying

to get AKC and GSDCA funding to study and possibly

identify a genetic marker for pancreatic acinar

atrophy in the breed.

The Animal Health

section of HelpLine (UK), autumn 1999 issue had

several articles on frank pancreas insufficiency and

malabsorption. That reported on a test for the

specific detection of pancreatic insufficiency,

using a trypsin method (TLI) from a single blood

sample. This replaced the fecal test, which had

proved inaccurate. Differential diagnosis of

pancreatic insufficiency and other small intestine

disease are sometimes difficult since clinical signs

can be similar. Many problems that befall the GSD

point to autoimmune conditions; research was carried

out by Dr. D. Williams in the U.K. Pedigrees have

been requested by veterinarians working on this

problem, and a clearinghouse for information has

been set up by Dorothy Cullum, 15 North Road,

Brentwood, Essex, England. Chronic intestinal

disease, called overgrowth of intestinal bacteria in

the UK, and probably the same thing that the U.S.’

Dr. Chuck Kruger dubbed “toxic gut syndrome”, is

also being studied in Britain, and has been found to

be a particular problem in young dogs. Treatment

with high dosage of antibiotics over a long term has

been claimed to have a good success rate.

Malabsorption or poor

digestion and stool condition are frequently seen in

the GSD, and in my experience, has been more so in

the heavily linebred typical lines in American-bred

dogs since the 1970s. These symptoms can be caused

or exacerbated by physical or emotional stress,

change of food, and other things. I suspect that

dogs with subclinical weakness in immune systems or

pancreatic function may be most likely to show these

reactions. I know that my strongest-character dogs

over the years have also been able to eat almost

anything without diarrhea. Others have also

proffered the theory of an abnormality in the immune

system. Such dogs are apparently more likely to show

symptoms like increased susceptibility to bacteria,

intolerance to change in diets, ravenous appetite,

reduction in body weight or failure to gain,

diarrhea, greasy-looking feces with possibly

undigested cellulose as well, and an “unthrifty” dry

coat. The usual response by breeders and vets is to

try the enzyme supplements and/or something like

Hills Prescription Diet. But there are about as many

stories of failure as there are of successful

(though tricky, difficult) control. Some believe

that an increase in roughage or “bulk” is needed in

order to “keep the food in the system” long enough

for the digestive system to do its work, but others

say that more bulk or roughage tends to move the

contents along a little faster. Also, we are told to

feed our affected dogs low-fat foods.

Some owners with

access to slaughterhouses claim some benefit from

feeding raw pancreas, but there is not enough data

with scientific controls to consider this anything

more than anecdotal testimony. This is not to

discount testimonials, though, as these can lead to

success and may be incentive for scientific

corroboration. One reader in the UK tried the

natural pig pancreas plus roughage route, and said,

“It [pancreas from the abattoir] is no more

unpleasant to handle than any other meat from the

freezer, costs half the price of powdered enzymes,

the dog absolutely loves it and appears to be more

effective than any man made preparation on the

market! He is not requiring as much food, as he is

obviously absorbing what he needs from his diet now.

He is not full of wind, and he is now producing

approx. 1/3 of the amount of faeces that he did on

the powders. I have also noticed that he is no

longer ravenously hungry and has actually left some

of his dinner on a few occasions.” On the other

hand, many experts say that you should reduce the

amount of non-digestible fiber in the diet for dogs

with pancreas problems.

If you choose the

expensive specialized EPI diet foods from Hills,

Eukanuba, or others, check the labels and prices —

they are “out of sight”. People who treat their EPI

dogs for the rest of the dogs’ lives can spend about

$1,000 to $1,500 annually for the enzymes alone. If

you go along this road, you will have to “soak” the

ration for a while, to give the enzymes time to work

— longer for the dry rations than for the canned.

The enzymes have their greatest effect after about

20 minutes.

Warning: you can spin

your wheels for years on the abundance and infinite

variety of nutritional advice. Many claims are

entirely unrelated and coincidental to results, but

people who are desperate will tend to try them all.

One correspondent told me that, after initial help,

she was no longer getting satisfaction by using just

the enzymes; her dog’s stools were getting poor

again. Later, she found good maintenance results by

supplementing with folate, vitamin B-12, banana,

live-culture yogurt, oatmeal, baked yams, and

flaxseed oil twice a day, in addition to “one

Cimitadine tablet (brand name is Tagamet) morning

and evening three times a week”. (Cephaloxin 500mg

two or three times daily, depending on the

situation, is sometimes administered for two weeks.)

This diet change had followed the Texas A&M College

of Vet Medicine’s suggested treatment with

cobalamine folate. Cobalamine is vitamin B-12, and

folic acid (obtained synthetically or in liver,

green leaves, and yeast) is essential to the

friendly lactobacillus in the gut, in combination

with which it inhibits malabsorption. That lady did

not see a turn-around in condition until more B-12

was added to the vet school’s recommended treatment.

She found that 2,000 milligrams of folate and a

fourth-teaspoonful of liquid B-12 with the dog’s

light meals three times a day gave marked

improvement It appears that occasional (quarterly,

for example) antibiotic treatment to kill unfriendly

bacteria, followed by folate and yogurt to encourage

the lactobacillus, is highly thought of by

veterinary nutritional specialists. I am a fan of

vitamin E, having seen benefits in many areas, so I

always recommend that people also give one or two

400-IU capsules a day of Vitamin E to help boost the

immune system.

Most people make a

distinction between EPI (Exocrine Pancreatic

Insufficiency) and pancreatitis, some saying that

dogs can recover from pancreatitis, rather simple

inflammation of the pancreas, and that when the

pancreas begins to atrophy, the only thing you can

do is supplement with digestive enzymes like Viokase

V or with Pancreazyme. I tend to believe the two

conditions are more intrinsically linked. Canned dog

foods, even the non-prescription brands, are said to

be easier for the EPI dogs to digest than is dry

kibble. The EPI dog is unable to efficiently digest

carbohydrates, protein and especially fat. The

condition is also called acinar atrophy, the word

“acinar” referring to the physical tissue structures

that make up lobules in the gland. When the pancreas

atrophies, it loses ability to function in its

digestive mode; it apparently does not interfere

with insulin production, which is its endocrine

function carried on by different types of cells.

Some dogs do become diabetic as well, but this may

be entirely unrelated.

I have been told that

the statistics on EPI dogs indicated that 1 in 5

pups born to an EPI-affected dam would eventually

show signs of EPI. There seem to be a higher than

average number of stillborn pups, as well. Whether

this has anything directly (genetically) to do with

EPI, or is a reflection on the poorer physical

condition that leads to uterine inertia, is hard to

say. By the way, on this website you are now

surfing, you might also find my article on uterine

inertia and the use of oxytocin.

The test that your vet

or his contracted lab will perform will give you a

reading of what is called Tli. This is an enzyme

blood test that determines the level of digestive

enzymes present. It can vary from day to day,

increasing and decreasing and varying within the

same day. The scale on this test from low to high,

is 5.0 to 35.0 while GSD’s rarely test over the 5.0

to 8.0 range. At Texas A&M, the Researcher told me

that they have found that dogs that normally test

below 8.0 will most probably become EPI positive. Of

course they are talking about all breeds, and we

must remember that there are breed differences. The

GSD, for example, has a higher packed-cell volume

than other breeds, and it is likely the Tli range

that is abnormal for others might be more normal for

GSDs. The disorder might remain fairly unnoticed or

asymptomatic until it reaches a Tli much below 5.0,

then the dog typically begins to get voraciously

hungry and has terrible diarrhea with a sour odor,

many times a day. Severe weight loss is an

indication that the dog is starving to death. The

fur loses pigment and gloss, becomes dry and brittle

and often is lost to some extent, and Staphylococcus

infection scabs may appear on the skin, because the

compromised immune system doesn’t allow the dog to

fight off the infection. The symptoms of EPI mostly

show up when the TLi is down around 2.5 to 3.0. In

most breeds perhaps, any dog that tests at even an

8.0 will be at high risk for EPI. So, most dogs will

be diagnosed with EPI when Tli is at 8.0 or less,

and perhaps 0.4 or lower for GSDs. If a dog is found

to be within the normal Tli range (for GSD’s 5.0 to

8.0) but exhibits symptoms such as much flatulence,

diarrhea that is light brown/yellow to clay color

from time to time, the dog should be tested for

levels of Lipase, Protease and Amylase.

The genetics of

pancreatic disorders may confuse, because the

expressions are highly variable. Some can carry the

trait and never develop EPI, while others show

symptoms, although the genotype may be similar. The

wisest recommendation is that such dogs not be bred

as they most certainly carry the recessive gene.

They are currently looking for a “marker” in the

families of dogs they’ve been working with over the

last couple of years. Before breeding, one perhaps

should have the TLi test done, and get a hint of the

possibility of carrying the gene. If you breed two

that are carriers together, you risk as much as the

entire litter having EPI. I once bought a full

brother of a famous champion named Shiloh; My

“Harry” was a beautiful animal with excellent hips,

but he developed the pancreatic disorder and had to

be controlled as much as possible with the enzyme

powder. I had sold a co-ownership in him before the

disorder developed, and he was killed in a car crash

before years of treatment and follow-up would have

been completed. Some others with close relatives

also reported pancreatic insufficiency in their

dogs. One vet I know of told his client that EPI “is

not considered being ill — merely a genetic

condition.” Merely a matter of semantics? To me,

pancreatic insufficiency is an abnormality that

calls for removal from the gene pool, whether the

dog has a mild case or asymptomatic most of the

time. I have found that most vets take but a modicum

of hours of nutrition and practical genetics classes

in vet school, and then forget most because they

don’t use it every day. Breeders, especially those

with a science background, are more reliable sources

of information, I think. Unfortunately, not many

people who offer their EPI males at stud admit or

declare any cautions about their dogs. As one

observer quipped, “It’s funny isn’t it, that those

who deny all those things have Viokase-V on the

shelf in their back rooms?” Yes, in spite of the

fact it is good for various causes of diarrhea, it

is so much more expensive than Kaopectate, that it

makes you wonder.

Connection between PI

and GDV? — There have been reports from dog owners

indicating that many episodes of EPI begin with a

bloating incident, or with a gastroenteritis, marked

by vomiting and blood tinged diarrhea. One who had

“chatted” on the Internet with many GSD owners in

the UK and the USA said, “From the general info

collected, the dog first bloats, which often leads

to torsion of the gut, which of course requires

surgery for a tacking of the stomach, and this is

usually followed by a full blown episode of EPI

within a few months of the surgery.”

Intussusception — In

very young pups (and other animals including humans)

the intestine can invaginate (one part slips inside

another). The condition, also referred to as

“telescoping intestines”, also occurs in adults, but

not as frequently. Most common immediate causes

include worms, obstruction by indigestible

materials, garbage, or toxic substances. The German

Shepherd seems to experience a high incidence of

this disorder and I believe there is a genetic

propensity, a familial trait, in certain bloodlines.

Diarrhea and soft

stool — Diarrhea can be a symptom of any number of

disorders from cancer to overeating, but is most

often associated with disease or parasitism of the

small intestine. Diarrhea or loose stool is quite

common in the German Shepherd Dog, even when no

physiological disease has been identified. However,

since this is not a normal condition, the owner

should make a sincere attempt to find and attack the

cause. Some of the causative factors in true

diarrhea are: pancreatic insufficiency, chemical or

mechanical irritation of intestinal linings,

parasites, microorganisms, and a psychosomatic

condition related to the “high-strung,” emotional

make-up of the German Shepherd Dog. Foods that can

cause loose stool include milk (if suddenly

introduced into the diet), excessive liver, fats,

and those with a high fiber content. However, simple

overeating is perhaps the most frequent culprit.

Most people overfeed their dogs.

Soft to runny stools

may be an indication of a general inflammation of

the stomach and intestines known as eosinophilic

gastroenteritis. It is treated symptomatically with

something to coat the lining, plus perhaps a steroid

and Kaopectate, until the dog “heals itself.” Many

veterinarians and owners administer Pepto-Bismol,

also. In the case of very young puppies with watery

stool or repeated diarrhea, rush to your veterinary

clinic with the pup and the stool samples. Most of

the time the cause of diarrhea in a young puppy is

serious, such as parvo or coccidiosis, perhaps with

hookworm as well. The Campylobacter bacteria cause

some cases of acute or chronic diarrhea, and most

labs would have no trouble identifying this

infection. Generally watery diarrhea is not an

indicator of “campy”. Erythromycin antibiotic is 90%

effective, although resistant strains may be

evolving.

Even giardia can be

quite dangerous, if the pup is young and has been

exposed to other challenges, such as being wormy,

stressed, or otherwise weakened. Giardiasis is

marked by watery diarrhea with a uniquely acrid

“bloody” odor, that experienced breeders can

identify quite easily even before a stool sample is

analyzed. Giardia is a protozoan disease; i.e., it

is caused by a single-celled “animal” flagellate

parasite, so-called because it is highly motile,

having a tail. The Merck Veterinary Manual describes

it: “Transmission occurs in the cyst stage by the

fecal-oral route. Incubation and pre-patent periods

are generally 5 to 14 days. Giardia cysts survive in

the environment and thus are a source of infection

and reinfection for animals, particularly those in

crowded conditions... prompt removal of feces from

cages, runs, and yards will limit environmental

contamination. Cysts contaminating the hair of dogs

and cats may be a source of reinfection.” Regarding

treatment, the manual says “Flagyl ™ (metronidazole)

is about 65% effective” (in removing cysts from

feces) and if administered “for 3 days, effectively

removes giardia cysts from feces of dogs; no side

effects are reported.” By the way, these oocysts are

much smaller than worm eggs, and require much higher

magnification to find them; still, they are not shed

every day, so it may be wise to start treatment and

then wait for a three-to-five-day combined stool

sample to be checked by your vet. Despite the “low”

rate or ridding the body of cysts, many vets prefer

Flagyl. The success rate is reportedly declining as

giardia is now demonstrating resistance to the drug.

In addition, it may be a little hard on young

puppies, with some neurological side effects.

Panacur (fenbendazole)

is relatively pricey and seems to be sold only in

large-volume jars from the usual vet supply

catalogs. For giardia, Panacur is considered a

static drug, 100% effective in clearing cysts from

feces in 3 days (the cysts are the infective part),

with no side effects reported, and is safe for

pregnant and lactating animals. In the lab, giardia

did not develop resistance to fenbendazole. It does

not have a repelling taste. A field representative

for Intervet, the company that manufactures Panacur,

admitted that Flagyl may be preferable for the

occasional dog that has general stomach distress.

With either one, a 5-day dose has been reported by

some to be effective when the 3-day regime was not.

I would also recommend

that you ask your vet about Albon™ (sulfamethoxine)

which is much more effective, although for a

different reason, and should be given for 15 to 21

days. The sulfa drugs do nothing to the Giardia

organism itself, but they do combat the secondary

bacterial infections that are probably the real

killers of puppies. Such an approach allows the pup

to regain enough health to withstand the protozoan,

even though it may be retained in the body for a

while. It is more readily available, probably lower

in cost, and in widespread use. A disadvantage in

any sulfa drug is a number of adverse side-effects,

but I have not had any problems, probably because I

do not keep dogs on the medication longer than

recommended, and have genetically strong breeding

stock.

There are a few

less-often used: Valbazen (albendazole) is about 90%

effective in removing cysts but has been implicated

in birth defects, suppression of the immune system,

and destruction of red blood cells. .Atabrine

(quinacrine) also has unpleasant side effects. Some

have recommended a Giardia Lamblia vaccine for dogs

with persistent or repeated cases.

Toxic gut syndrome (TGS)

— This disorder has been identified as a specific

syndrome, with some similarities to other disorders

such as intestinal volvulus, which may have been

blamed for death when TGS was the real villain. The

German Shepherd Dog has a higher packed cell volume

(number of blood cells per unit of blood) than do

most other breeds, with 50 to 60 percent “solids”

compared with 40 to 45 percent. When such a dog

becomes dehydrated, thickened and/or lessened blood

supply to the small intestine increases growth of

bacteria that are always present there. These

Clostridium and E. cold bacteria produce such

quantities of toxins that the dog is unable to get

rid of them fast enough, and death by poisoning

occurs. By the time owners see symptoms such as

discomfort when the abdomen is touched, attempts to

vomit, and excessive salivation, it is probably too

late. Prevention may be accomplished through dietary

means (feeding Lactobacillus acidophilus, yogurt, or

cultured buttermilk), or by the same toxoid vaccine

that is given to lambs to prevent Clostridium

perfringens types C and D. As research is done on

this recently defined syndrome, more will become

known as to the best treatment.

Other problems —

Ulcers have been diagnosed too frequently in German

Shepherds and may be related to pancreatic problems

or other causes: it’s difficult to tell, when

several conditions exist at once, whether one is the

cause or effect of another. Necrotic bowel syndrome,

a disorder of unknown cause, is diagnosed usually on

autopsy, when part of the intestine is found to be

dead and rotting away. This condition may be

synonymous with or overlap intussusception or other

diseases. It takes a small toll, mostly among

heavily linebred German Shepherd Dogs.

Eosinophilic

ulcerative colitis — This syndrome is most common in

Cocker Spaniels and German Shepherd Dogs. If your

pup or adult has intermittent to constant diarrhea,

with or without blood, and does not respond to

treatments for the more common disorders, this

disease may be the cause. Initial treatment may

include corticosteroids, antibiotics, and

antispasmodics to see if the symptoms can be halted.

Irritable colon — Also

known as spastic colon, this disorder with mucus in

or on the surface of soft or frequent stools may be

the result of stress. The best cure is prevention —

breed stable temperaments and build confidence in

puppies.

Polyps — Rectal polyps

are little round or teardrop shaped red to purplish

balls. Sometimes they are clustered like tiny

grapes, and are found very close to the anal opening

or further inside the rectum. They should be

surgically removed, since they rupture easily and

are a potential site for infection. A drop of bright

red blood recurring on the end of stools is a sign

that you should have the dog examined for polyps.

****************************************************

The author is a breeder since 1945, a teacher and

lecturer in canine topics, and dog show judge. His

book, The Total German Shepherd Dog, is available

from

http://www.Hoflin.com and he can be contacted at

Mr.GSD@Juno.com |